https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(20)31027-8/fulltext

The evolution and sustenance of our planet hinges on a symbiotic relationship between humans, animals, and the environment that we share—we are interconnected. (The warm and fuzzy start.) However, this past century has seen human dominance over the biosphere, manifest in technological innovations, accelerated mobility, and converted ecosystems that characterise industrialisation, globalisation, and urbanisation. These developmental trajectories have advanced human health in unprecedented ways. However, they also make humans increasingly vulnerable to contemporary global health challenges, such as emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases, (a false assertion as we have less natural infectious disease now worldwide than ever before) as shown by the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, antimicrobial resistance (AMR), and the increasing burden of non-communicable diseases. (Again, an evidence free assertion—that technology leads to chronic illness, when it is probably the cheap factory food that is the culprit.) These challenges are further impacted by climate change, poverty, conflict, and migration.

The apparent dominance of the human species comes with a huge responsibility. Thus, in our quest to ensure the health and continued existence of humanity, consideration must be given to the complex interconnectedness and interdependence of all living species and the environment—the concept of One Health. One Health highlights the synergistic benefit of closer cooperation between the human, animal, and environmental health sciences, as well as the importance of dismantling disciplinary and professional silos. The One Health concept has been recognised and promoted by the UN, the G20, and WHO, among several others. The Sustainable Development Goals in themselves can be understood as embodying a One Health strategy aimed at healthy people living on a perpetually habitable planet. (The planet may become uninhabitable if human dominance is not curbed.)

The Lancet One Health Commission comprises 24 Commissioners (appendix) and several researchers from multiple disciplines from around the globe. The Commission's inaugural meeting was held in Oslo, Norway, in May, 2019. The Centre for Global Health at the University of Oslo, Norway, hosts the northern secretariat, with the support of the Center for Global Health at the Technical University of Munich, Germany. The Global Health group at the Kumasi Centre for Collaborative Research in Tropical Medicine on the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology campus, Kumasi, Ghana, hosts the southern secretariat. The Lancet One Health Commission aims for transdisciplinary and interdisciplinary collaboration to promote original thinking and generate solutions to the complex global health challenges of modern times, most of which require a One Health approach. (An evidence-free assertion that we cannot solve global health challenges without One Health—why would anyone believe that?) The Commission's work is expected to offer a recalibrated understanding of the ways in which these global health challenges are implicated within the complex interconnectedness of humans, animals, and our shared environment, and to provide an approach for harnessing this knowledge to ensure a sustainably healthy future for all species, and the planet we inhabit. (Just leave it to us to provide a new, untested One Health understanding and approaches to the major problems of civilization.)

The main objective of The Lancet One Health Commission is to synthesise the evidence supporting a One Health approach to enhancing health within an environment shared by humans and animals. (In other words, we are going to try to gather and present evidence that will support the assertions we just made about the benefits of One Health.) The Commission's work will explicate the significance of a One Health approach for policy by engaging transdisciplinary expertise and perspectives from both the public and private sectors. The Commission will explore global health challenges through a One Health lens, directing attention to infectious diseases, AMR, and non-communicable diseases—the latter of which have often been left out of the discourse on One Health.

In proposing policy, implementation, and governance recommendations, (the Commission will emphasise sociopolitical dimensions of health that are crucial for engaging and educating communities. Similarly, the Commission will promote leadership to build consensus (we will train a young crop of impressionable leaders like the WEF does who will be the soldiers to carry out our plans) among disparate sectors and foster champions for cohesion and change. Novel financing mechanisms will be assessed because these are key for building resilient health systems nationally and internationally.

Conclusions from the Commission are anticipated to be integrated in policy briefs, international guidelines and protocols, and various high-level global health resolutions. (We plan to shove these ideas down your throat.)

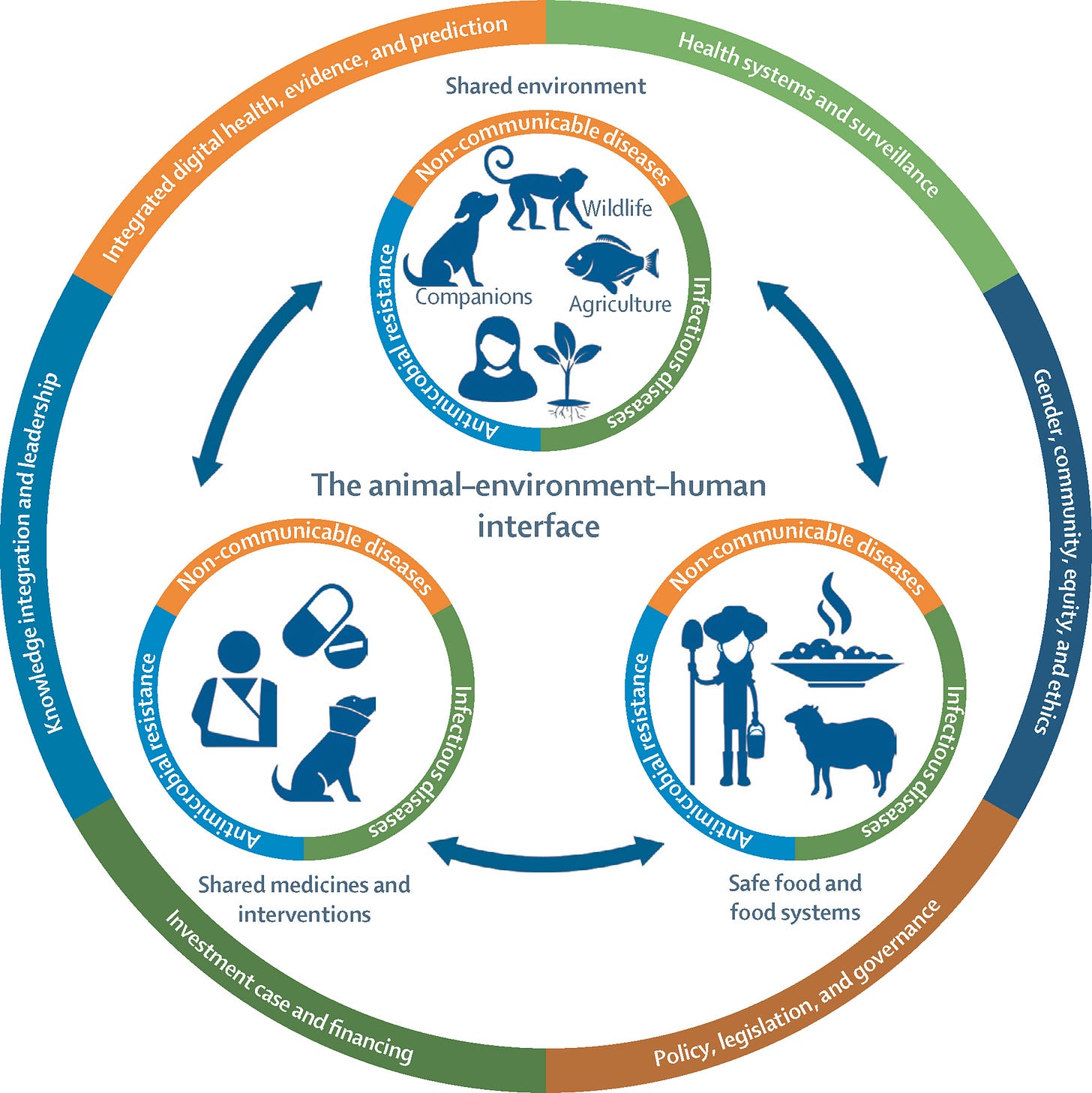

At the core of The Lancet One Health Commission's work is our recognition of several possible approaches to examining the animal–environment–human interface, which we distill into three distinct but interrelated dimensions (figure).

(The most pathetic part of One Health is the awful graphics. Since One Health offers nothing of value except ideology to assist the WHO in declaring jurisdiction over the planet, the graphic artists are unable to produce graphics that have meaning and value. However, the outer circle does tell you what One Health is really interested in.)

The first dimension is the shared environment. We will consider how animals, including livestock, wildlife, and companions, share a common environment with humans in both rural and urban settings. We further explore the positive and negative implications of human activities and human–animal interactions for the shared environment. Within this space, zoonotic and emerging infectious diseases, as well as non-communicable diseases and mental health, will be considered.

The second dimension is safe food and food systems. People rely on animals both as food and to help produce food. As such, the link between One Health and food safety and security will be explored. Among other things, the Commission will critically examine evidence for the hypothesised link between AMR and agricultural practices and we will proffer policy recommendations for scientific work to measure the association using innovative research methods.

The third dimension is shared medicines and interventions. Several drugs used to treat health conditions in humans originated from animal agriculture—eg, praziquantel and ivermectin. The potential for a more integrated approach to the implementation of health interventions that target both animals and people will be explored. (It should be apparent that One Health is reaching hard for relevance with its 3 dimensions, but there is little relevance to be found.)

Each of these three dimensions will be examined in relation to infectious diseases, non-communicable diseases, and AMR (figure). Operationalising One Health will require integrated animal and human health systems, including surveillance; robust modelling efforts that use big data for animals, humans, and plants; and engagements with digital health. Now more than ever with the COVID-19 pandemic, concerted knowledge and evidence generation must inform and catalyse responsive leadership, context-driven governance, progressive policy, and legislation that are sensitive to gender, community, equity, and ethics (figure). This work is vital for ensuring a sustainably reconnected approach to defending and synergistically enhancing the health of humans, animals, and our shared environment.

(Did you gain any understanding of how One Health might provide value to any animal, human or plant? I sure didn’t.)