- When to reopen the economy?

- When to send children back to school?

- Will there be a second wave, or even a third wave, as occurred with the 1918 swine flu pandemic?

Those questions demand answers, but our leaders are giving us none. And we can't even create useful hypotheses to test, because we have not been given the essential data needed. Yet there are numerous government agencies whose job it is to collect these data. They are silent. And the spokespeople on the podium with Trump every day fail to address these issues.

- Can you be reinfected after recovery from Covid-19?

- How likely are the a) PCR tests and b) antibody tests, to accurately determine if you a) have the disease and b) have had it and are now immune?

- How many Americans have already had this infection, and are now immune?

- What percentage of cases are asymptomatic?

- What is the true mortality rate of Covid-19 overall, and the mortality rate in different age groups?

- What is the infectious dose (the number of viral particles needed, on average, to cause infection)?

- What do independent scientists think of the data emerging on various treatments?

Mortality rates

The data publicly available are very limited. The Chinese felt that one swab tested by rtPCR was insufficiently sensitive to rule in or out an active infection with Covid-19. But most Americans, if they were eligible to be tested, only received one swab.

Based on the guidelines that specified who could be tested, we can assume that the majority of those who were tested had symptoms consistent with Covid-19. Of all 3,723,634 Americans tested, 737,319 are positive today, or 19.8%.

As of April 19, using the JHU database, 15% of those Americans who tested positive were hospitalized. This is consistent with the Chinese data. The gross mortality rate (total deaths divided by total diagnosed cases) is 4.8%. This too is consistent with the Chinese data. [Just after I wrote this a large number of nursing home deaths were added to the US total, raising the rate to 5.3%.]

Note that western Europe has considerably higher mortality rates than we do (2-3x higher) when calculated this way, which could be a reflection of the fact that they are further along the epidemic curve than we are. In other words, their deaths peaked before ours did.

Eight days ago, the US mortality rate calculation was 3.8%. Today it is 5.3%. Our rate will continue to rise until we are past the peak of the curve.

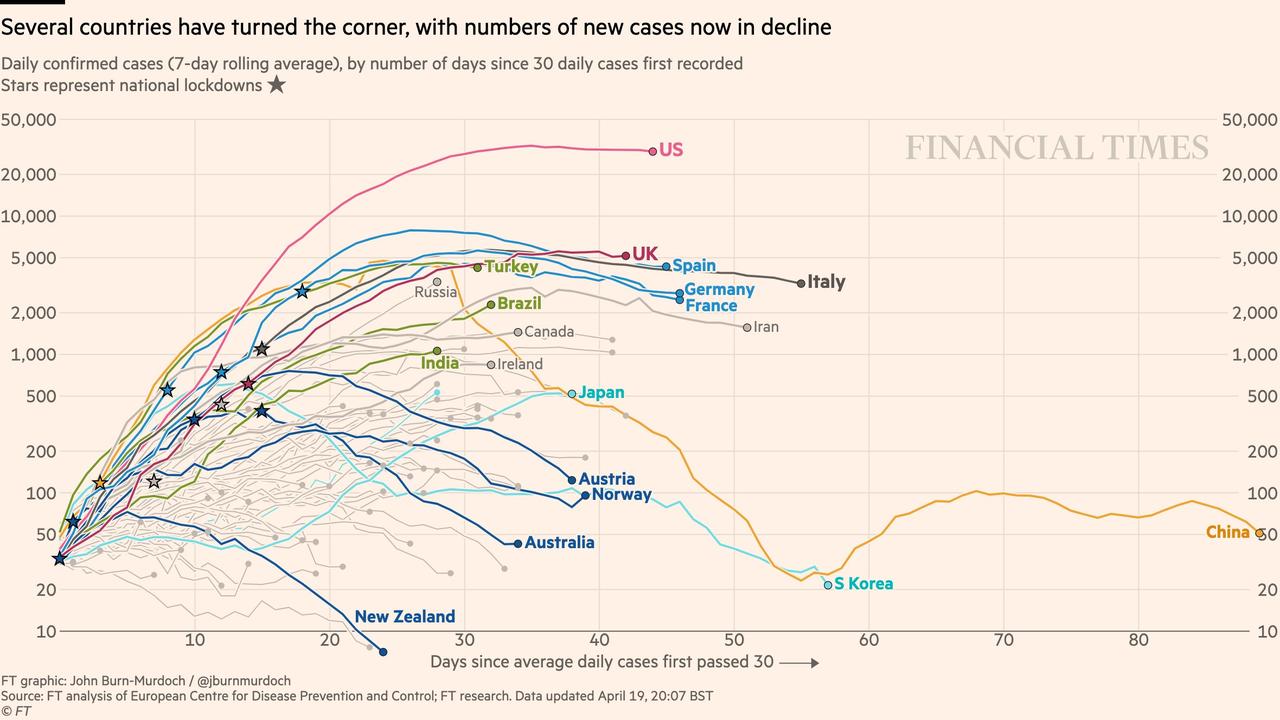

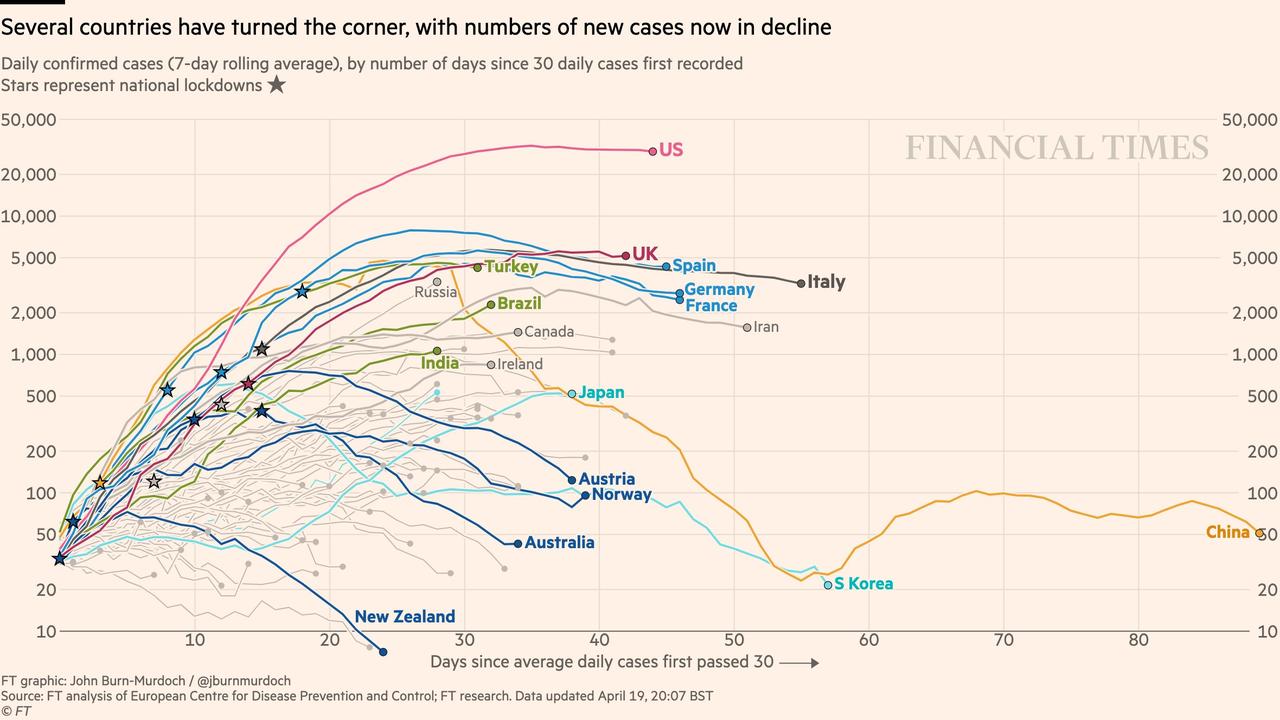

And this ZeroHedge graphic uses a log scale to show that all countries have slowed the rate of growth of new cases, which were growing exponentially at first. For most countries, deaths are lessening daily. The US rate is about 1900 deaths/day, and has been stable for the past 2 weeks. But here again, while progress is good, this progress was made at the expense of quarantine. While the rate at which new cases are diagnosed is not rising, it is not dropping significantly, either.

Back to mortality rates

Europe's high mortality rates could reflect the fact their populations are older, and/or that US medical systems were not overwhelmed in the same way that occurred in parts of Europe.

BusinessInsider created a chart of mortality rates by country 5 days ago. Rates ranged from 12.8% in Italy and Belgium to 2.5% in Germany, where testing was done more widely.

But it is not yet clear what the true mortality rate is anywhere, since we have not done sufficient population sampling to know what percentage of cases are asymptomatic. And because of the long lag (2-3 weeks) between diagnosis and death, there are deaths still to be counted from those recently diagnosed.

Population sampling

Population sampling goes on all the time. Patients get tested for one thing, or they donate blood, and their specimen may get tested for something else as well, as part of a research project. For example, sampling for coronavirus antibodies in blood donors started early, during the Seattle outbreak, and has expanded to a number of cities. Science magazine spoke with Michael Busch, a researcher, about his ongoing serosurveys.

Eight days ago, the US mortality rate calculation was 3.8%. Today it is 5.3%. Our rate will continue to rise until we are past the peak of the curve.

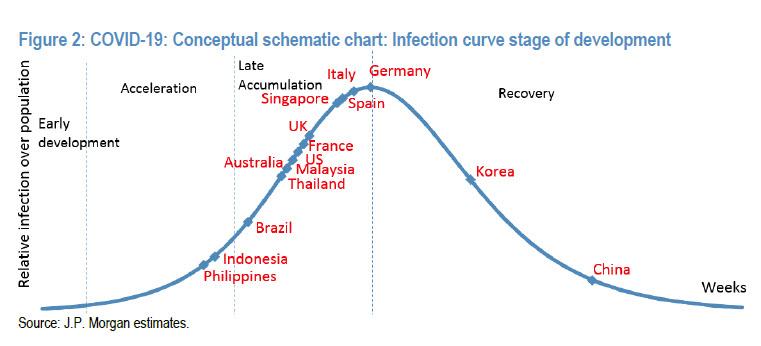

Here is a schematic from ZeroHedge showing where countries lie on the epidemic curve. But this is where countries lie after social distancing. No one knows what the curve would look like under normality.

Back to mortality rates

Europe's high mortality rates could reflect the fact their populations are older, and/or that US medical systems were not overwhelmed in the same way that occurred in parts of Europe.

BusinessInsider created a chart of mortality rates by country 5 days ago. Rates ranged from 12.8% in Italy and Belgium to 2.5% in Germany, where testing was done more widely.

But it is not yet clear what the true mortality rate is anywhere, since we have not done sufficient population sampling to know what percentage of cases are asymptomatic. And because of the long lag (2-3 weeks) between diagnosis and death, there are deaths still to be counted from those recently diagnosed.

Population sampling

Population sampling goes on all the time. Patients get tested for one thing, or they donate blood, and their specimen may get tested for something else as well, as part of a research project. For example, sampling for coronavirus antibodies in blood donors started early, during the Seattle outbreak, and has expanded to a number of cities. Science magazine spoke with Michael Busch, a researcher, about his ongoing serosurveys.

We’re developing three large serosurvey studies. We need to do them at regular intervals to detect ongoing incidence, to determine if antibody responses are waning, and to assess herd immunity.

The first one, which will be funded by the National Institutes of Health, is already underway in six metropolitan regions in the U.S. It was started in Seattle when that outbreak happened, then New York City, then we quickly kicked in the San Francisco Bay area, and now we’ve added Los Angeles, Boston, and Minneapolis. Colleagues at regional blood centers are each saving 1000 samples from donors each month—often it’s just a few days each month—and they’re demographically defined so we know the age, the gender, and, most important, the zip code of the donor’s residence. Those 6000 samples, collected each month starting in March and for the next 5 months, will be assessed with an antibody testing algorithm, which we’re still finalizing, that will help us monitor how many people develop SARS-CoV-2 antibodies over time. That will show us when we’re going from, say, a half a percent to 2% of the donors having antibodies.

That will evolve into a national survey. With support from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], we’ll conduct three national, fully representative serosurveys of the U.S. population using the blood donors...

It would be nice if, while they are developing their algorithm, they would let us know some of their raw data.

A recent Chinese study found that 78% of new infections identified were asymptomatic, in contrast to earlier Chinese data suggesting few cases were asymptomatic. A Dutch study of blood donors has found 3% have antibodies to SARS-CoV-2. A Stanford study, which has been much criticized, found antibodies present in 1.5% of Santa Clara county residents, in a nonrandom sample. I can't believe that the CDC or other federal health agency, or military agency, has not already done widespread sampling, whose results have so far not been reported.

If it is true that less than 5% of Americans are currently immune to SARS-CoV-2, then reopening the country will lead to a bigger wave of illness and deaths than we have so far experienced. There is no way to gain a more immune population without more exposure and more disease, unless a successful vaccine appears.

Trying to wipe the virus out through aggressive case-finding, as Dr. Frieden suggested, would be helpful (if it could be accomplished in the US) but it simply will not happen everywhere else in the world, since many countries lack the infrastructure to do so. The fact that those infected with SARS-CoV-2 can spread the infection before they have symptoms, and after their apparently recover, makes case-finding and quarantine even trickier. You would need to repeatedly test people, and we do not have the materials to do so. Are any of the multitude of federal agencies (whose role is pandemic preparedness) figuring out how many machines, reagents, tubes, swabs, trained lab personnel it would take to do repeated tests on the bulk of Americans? And since the rest of the world will be attempting to do the same thing, we need to account for the fact that they too will be seeking the same materials. Where are these items made? What raw materials are used? How big is the world supply? How quickly can they be made? And who is in charge of identifying suppliers and making sure adequate supplies can be manufactured to meet demand, not just today, but potentially for a year or more.

A lot of money and multiple federal agencies, as well as many private companies, are working on a vaccine. It has been reported that 70 vaccines are in development. But it is important to note that no coronavirus vaccine has ever succeeded, despite vigorous efforts. Four different approaches to coronavirus vaccines failed in the past. The US' foremost vaccine boosters (Doctors Gregory Poland at Mayo, Paul Offit at U Penn and Peter Hotez at Baylor) have issued warnings about this vaccine, noting that previously developed vaccines led to more severe disease in experimental animals, when they were vaccinated and later exposed to SARS. More and more, experts doubt that a vaccine will appear in time to make a dent on this pandemic.

Plan A: a quarantine that should have been aligned with measures to prepare us for what happens after the quarantine

The purpose of the quarantine, in my view, was to stop transmission while buying time. We didn't know who might be contagious, so everyone needed to be locked down for at least a 14 day quarantine, at which point, the thought was that we would know who got symptoms and thus control the vast majority of cases. We needed to buy time in order to get our medical facilities up to speed, figure out how to obtain the drugs we would need, retrain staff on the details of the Covid-19 disease, retrain staff on ventilator, ECMO, dialysis management, and train staff on the safe use of PPE. We needed to reorganize our medical facilities so those infected could be segregated from those with other medical conditions, without passing the virus on to them.

We needed to make arrangements to surge the production of PPE to properly protect healthcare workers, build ventilators, ECMO devices, and (now we know) build dialysis machines for short-term use, since the virus infects the kidneys and often leads to kidney failure.

We needed to buy time to determine which drugs worked best, and start a surge capacity to produce them. Drugs that are effective prophylactically, or at an early stage of illness, will be the next best thing to herd immunity and a safe vaccine, both of which are elusive. More on that as data get released. In India, a weekly dose of chloroquine is being trialed as a preventive for healthcare workers, similar to a dosing regimen used to prevent malaria.

Mostly, we needed to buy time to obtain accurate tests that would give us timely results, and we needed to begin testing the entire population. Running out of the simple dacron swabs and reagent to perform nasal sampling is ludicrous, four months into the pandemic. Who forgot to guarantee the availability of such simple equipment?

To a considerable extent, the time during which we have been quarantined has been wasted. We are unprepared to efficiently manage a larger surge of patients. We are plagued with partisan arguments about drugs. We have dozens of tests but their specificity and sensitivity are still in question, and FDA has yet to review most of them. The WHO has warned against relying on antibody tests. It has further warned that the presence of antibodies may not reflect immunity.

We have learned that a considerable number of cases are asymptomatic, while they may still spread disease, possibly for weeks. We have no idea who these people are and how many they are, nor the magnitude of the problem this poses.

Part 3 will continue the theme of missing and hidden information, and will start to envision a workable Plan B. The major issues with testing will be discussed in a subsequent post.

A recent Chinese study found that 78% of new infections identified were asymptomatic, in contrast to earlier Chinese data suggesting few cases were asymptomatic. A Dutch study of blood donors has found 3% have antibodies to SARS-CoV-2. A Stanford study, which has been much criticized, found antibodies present in 1.5% of Santa Clara county residents, in a nonrandom sample. I can't believe that the CDC or other federal health agency, or military agency, has not already done widespread sampling, whose results have so far not been reported.

If it is true that less than 5% of Americans are currently immune to SARS-CoV-2, then reopening the country will lead to a bigger wave of illness and deaths than we have so far experienced. There is no way to gain a more immune population without more exposure and more disease, unless a successful vaccine appears.

Trying to wipe the virus out through aggressive case-finding, as Dr. Frieden suggested, would be helpful (if it could be accomplished in the US) but it simply will not happen everywhere else in the world, since many countries lack the infrastructure to do so. The fact that those infected with SARS-CoV-2 can spread the infection before they have symptoms, and after their apparently recover, makes case-finding and quarantine even trickier. You would need to repeatedly test people, and we do not have the materials to do so. Are any of the multitude of federal agencies (whose role is pandemic preparedness) figuring out how many machines, reagents, tubes, swabs, trained lab personnel it would take to do repeated tests on the bulk of Americans? And since the rest of the world will be attempting to do the same thing, we need to account for the fact that they too will be seeking the same materials. Where are these items made? What raw materials are used? How big is the world supply? How quickly can they be made? And who is in charge of identifying suppliers and making sure adequate supplies can be manufactured to meet demand, not just today, but potentially for a year or more.

A lot of money and multiple federal agencies, as well as many private companies, are working on a vaccine. It has been reported that 70 vaccines are in development. But it is important to note that no coronavirus vaccine has ever succeeded, despite vigorous efforts. Four different approaches to coronavirus vaccines failed in the past. The US' foremost vaccine boosters (Doctors Gregory Poland at Mayo, Paul Offit at U Penn and Peter Hotez at Baylor) have issued warnings about this vaccine, noting that previously developed vaccines led to more severe disease in experimental animals, when they were vaccinated and later exposed to SARS. More and more, experts doubt that a vaccine will appear in time to make a dent on this pandemic.

Plan A: a quarantine that should have been aligned with measures to prepare us for what happens after the quarantine

The purpose of the quarantine, in my view, was to stop transmission while buying time. We didn't know who might be contagious, so everyone needed to be locked down for at least a 14 day quarantine, at which point, the thought was that we would know who got symptoms and thus control the vast majority of cases. We needed to buy time in order to get our medical facilities up to speed, figure out how to obtain the drugs we would need, retrain staff on the details of the Covid-19 disease, retrain staff on ventilator, ECMO, dialysis management, and train staff on the safe use of PPE. We needed to reorganize our medical facilities so those infected could be segregated from those with other medical conditions, without passing the virus on to them.

We needed to make arrangements to surge the production of PPE to properly protect healthcare workers, build ventilators, ECMO devices, and (now we know) build dialysis machines for short-term use, since the virus infects the kidneys and often leads to kidney failure.

We needed to buy time to determine which drugs worked best, and start a surge capacity to produce them. Drugs that are effective prophylactically, or at an early stage of illness, will be the next best thing to herd immunity and a safe vaccine, both of which are elusive. More on that as data get released. In India, a weekly dose of chloroquine is being trialed as a preventive for healthcare workers, similar to a dosing regimen used to prevent malaria.

Mostly, we needed to buy time to obtain accurate tests that would give us timely results, and we needed to begin testing the entire population. Running out of the simple dacron swabs and reagent to perform nasal sampling is ludicrous, four months into the pandemic. Who forgot to guarantee the availability of such simple equipment?

To a considerable extent, the time during which we have been quarantined has been wasted. We are unprepared to efficiently manage a larger surge of patients. We are plagued with partisan arguments about drugs. We have dozens of tests but their specificity and sensitivity are still in question, and FDA has yet to review most of them. The WHO has warned against relying on antibody tests. It has further warned that the presence of antibodies may not reflect immunity.

We have learned that a considerable number of cases are asymptomatic, while they may still spread disease, possibly for weeks. We have no idea who these people are and how many they are, nor the magnitude of the problem this poses.

Part 3 will continue the theme of missing and hidden information, and will start to envision a workable Plan B. The major issues with testing will be discussed in a subsequent post.

1 comment:

https://www.theguardian.com/world/live/2020/apr/20/coronavirus-us-live-cases-covid-19-donald-trump-andrew-cuomo-latest-news-updates

The administration official overseeing coronavirus testing efforts was pushed out of his vaccine development role at Texas A&M University over performance issues, according to a report from the Washington Post.

The Post reports:

[A]fter eight years of work on several vaccine projects, [Brett] Giroir was told in 2015 he had 30 minutes to resign or he would be fired. His annual performance evaluation at Texas A&M, the local newspaper reported, said he was ‘more interested in promoting yourself’ than the health science center where he worked. He got low marks on being a ‘team player.’

Now President Trump has given Giroir the crucial task of ending the massive shortfall of tests for the novel coronavirus. Some governors have blasted the lack of federal help on testing, which they say is necessary to enact Trump’s plan for reopening the economy.

That criticism has focused attention on Giroir and whether he can deliver results under pressure. His years as director of the Texas vaccine project illustrate his operating style, which includes sweeping statements about the impact of his work, not all of which turned out as some had hoped.

During two recent interviews with The Washington Post, Giroir blamed his ouster on internal politics at the university, not on any problems with the project.

Many public health experts have said that the economy cannot fully reopen until coronavirus testing becomes widely available; otherwise the country will risk seeing a surge in cases once stay-at-home orders are relaxed

Post a Comment